Time to Slay the Black Snake

The Journey

The sky in Wisconsin had been overcast for days on end when we left for Standing Rock. The clouds persisted all the way through Minnesota and into North Dakota, across the Great Plains, through the prairie pothole region, and into Bismarck. At Mandan, we stopped at an auto parts store to buy a snow scraper. It was a provident decision.

The journey from Bismarck or Mandan to Standing Rock would normally be routine: take Highway 1806 south as it edges along the Missouri River and Lake Oahe, an immense reservoir about 230 miles long. But a bridge on 1806 is blocked, which necessitates taking Highway 6 further west, a more roundabout route.

The bridge has been the focal point of the conflict that has raged throughout the fall between the Sioux of the Standing Rock Reservation and law enforcement officials and the corporations attempting to complete an oil pipeline across the Missouri River. On Sunday night, November 20, about 400 peaceful Water Protectors gathered on the bridge near the reservation, praying, singing and appealing to authorities to open the bridge to give those opposing the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) access to Mandan for supplies.

The Water Protectors were met by National Guard troops, local sheriff deputies, and police from various neighboring states. The police terrorized the Sioux and their supporters with water cannons, concussion grenades, rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray and sound cannons that cause severe headaches and loss of balance. About 300 people were injured, many suffered hypothermia from being drenched with water in subfreezing temperatures, an Indian elder went into cardiac arrest, and a Jewish activist, Sophia Wilansky, 21, was hit in the arm with a concussion grenade.

The Morton County Sheriff’s Department initially denied responsibility for Wilansky’s injury, which basically destroyed her entire left arm. Wilansky’s father said she had welts all over her body from being shot with rubber bullets, and that it took hours for an ambulance to reach her due to roadblocks.

We arrive exactly one week after this incident. We travel Highway 6, a winding road through beautiful country: it looks like the west, with rolling hills, buttes jutting up here and there, ranches and grassland. Suddenly we see the sun, a red fireball dipping behind the hills to the west. My companion remarks that it is the brightest red she has ever seen the sun, and it is the first we have seen of it in days. Perhaps it is an omen.

“We must go beyond the arrogance of human rights. We must go beyond the ignorance of civil rights. We must step into the reality of natural rights because all of the natural world has a right to existence and we are only a small part of it. There can be no trade-off.”

… John Trudell

We arrive at the Prairie Knights Casino and Resort that evening in time for a benefit concert with Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt and a number of Native American musicians. It is a powerful experience.

Among the musicians performing are members of John Trudell’s band, Bad Dog. Trudell was a Santee Dakota activist, poet, musician and actor who led the American Indian Movement (AIM) for most of the 1970s. He died on December 8 of last year. A founder of the spoken word movement, he fused traditional sounds with his poetry and rock & roll. He had toured with Browne and Raitt in the past for various native causes, and this night his band played some of his poems set to music.

When we leave the concert, it is snowing steadily. I’m not anxious to make the 70-mile trip south to our hotel room in Mobridge, South Dakota, but there are no rooms available at the casino this night. Several harrowing hours later, we arrive safely.

First Visit to Camp

We make it back to the casino and lodge the next morning. It is still snowing. We meet a young man named Ethan who is looking for a ride out to the camp. We take him with us and make the seven-mile trek north to Standing Rock. Ethan is here long-term and he orients us as we drive.

The encampment at Standing Rock is actually a number of different camps and it is an amazing sight to see and experience. The main camp here is Oceti Sakawan (the Great Sioux Nation). To the north, tucked within this larger camp, is the Red Warrior camp. Just to the south, on the bank of the Cannonball River, is the Rosebud camp. To the east a few miles is the Sacred Stone camp.

It is an immense occupation on land that the US government says belongs to it, but which the Water Protectors insist is part of the Standing Rock Reservation, unceded Lakota territory affirmed by the Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1851. Someone has noted that the last time there was a gathering this large at this spot was before the battle of the Little Big Horn.

It is an immense occupation on land that the US government says belongs to it, but which the Water Protectors insist is part of the Standing Rock Reservation, unceded Lakota territory affirmed by the Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1851. Someone has noted that the last time there was a gathering this large at this spot was before the battle of the Little Big Horn.

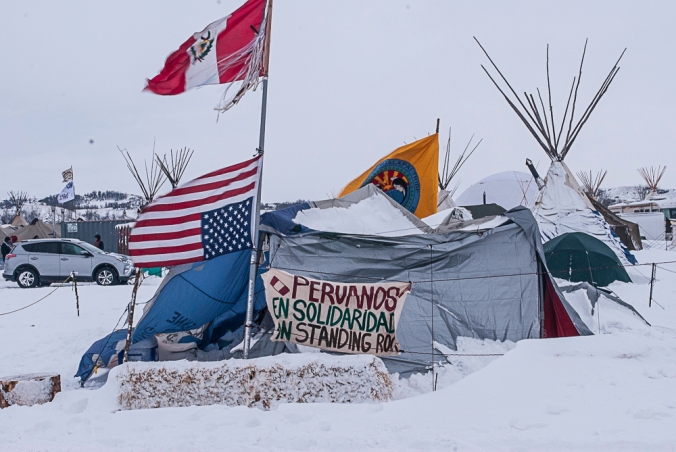

Flags and banners line the main road (Highway 1806), and flags line both sides of the main camp “road.” The flags represent Indian tribes across the country, as well as various organizations proclaiming their support for the occupation. There are more flags and banners everywhere you look and a maze of smaller “roads” crisscrosses the camp.

There are tipis, tents, yurts, old school buses and other forms of lodging scattered throughout. Some people are busy building more substantial wood structures to prepare for the harsh winter to come. There are nine kitchens in the camp, where communal meals are prepared and served. The two main gathering places are a large geodesic dome, where meetings are held, and the sacred circle, used for prayer and spiritual ceremonies, where a fire is always burning. And yes, there are porta potties.

To the north are hills, with floodlights pointing down on the camp. This is where law enforcement, I might as well call them the military, are staked out, watching our every move. Others have reported that helicopters are constantly hovering overhead, but I notice only one during our visit.

After exploring the camp for several hours, we leave before dark, returning to the casino where we have a room reserved for the next two nights.

Snowed In

It snowed all that night, and the next day. The wind howled and roared out of the northwest. It was a blizzard. No one was going anywhere. If anyone managed to get out of the parking lot, they got stuck on the road.

The lobby and halls and foyers of the lodge were filled with people: those who wanted to get to the camp and those who had come back for a respite. There was nothing to do but wait out the storm and strike up conversations with all the other “loiterers.”

All around the lodge there were signs posted indicating that people who were loitering and did not have a room might be asked to leave. (As far as I could tell, no one was ejected.) It seemed that some of the resort management may not have appreciated having a hundred Water Protectors and their supporters hanging out in the halls, perhaps discouraging other guests from Bismarck or elsewhere who come to gamble at the casino.

A rumor was circulating that DAPL had booked a large number of the 200 rooms in the resort in order to keep activists away. It seemed plausible. There were entire wings of the resort where there was nary a light on at night. The parking lot was half-empty, even before the blizzard hit.

I spoke with Paula, a woman from the Rosewood Sioux Tribe, who was visibly angry. “They turn off the elevator, the Wi-Fi reception, and other services,” she said. “Some people have cut deals with the oil companies.”

I spoke with Paula, a woman from the Rosewood Sioux Tribe, who was visibly angry. “They turn off the elevator, the Wi-Fi reception, and other services,” she said. “Some people have cut deals with the oil companies.”

George, a longhaired, soft-spoken man, said he too was concerned that DAPL was holding rooms but not using them. He confided that he was part of a team that was providing trauma care for elders and others, using rooms in the lodge when they could get them. After a major action, one hundred people might come through, he said.

I met Lucky Marlovitz while she was standing in line at the check-in desk, hoping to get a room for Tuesday night. Lucky, who is affiliated with a Catholic Worker community in Chicago, had traveled here with two others. After leaving the Twin Cities on Sunday morning, their car had wiped out on black ice in western Minnesota. The vehicle landed on its side in a ditch and was totaled, but a stranger in a small town lent them a car so they could continue their journey.

My longest conversation was with Carole Eastman Standing Elk, a 75-year-old elder from the Lake Traverse Reservation in the northeastern corner of South Dakota. Part of the Santee Dakota group, she now lives in California.

Carole complained that a community center in the town of Cannonball, which had been used by the Water Protectors to take showers, warm up and prepare meals, was now closed, even though people in the district had voted for it to remain open. The district chairman was in favor of the pipeline, she said.

Carole complained that a community center in the town of Cannonball, which had been used by the Water Protectors to take showers, warm up and prepare meals, was now closed, even though people in the district had voted for it to remain open. The district chairman was in favor of the pipeline, she said.

“Everyone should have a chance to come in and get warm and then go back,” she said. “In the old days, when we went to an action, we’d rent a room and then leave the door open so someone else could come and shower.”

An AIM member since she was 29 years old, Carole said people were gathered at Standing Rock because they recognized the importance of the Missouri River and the water. “If the river is polluted, how can people survive?” she asked. She said that Supreme Court decisions have upheld the rights of native people to the water. “It’s up to us to exercise our sovereignty.”

Don’t Blame the Natives: The Economics of Oil

The Dakota Access Pipeline is a $3.8 billion project that has been the subject of growing controversy throughout most of this year. The Standing Rock Sioux began a prayer vigil in April, and the conflict intensified in August when construction was scheduled to commence on the pipeline’s crossing of the Missouri under Lake Oahe, a half mile north of the reservation’s boundary. A lawsuit filed by the tribe, with the assistance of the environmental law firm Earthjustice, resulted in an injunction temporarily halting the Missouri crossing.

The Dakota Access Pipeline is proposed to stretch 1,172 miles from the Bakken shale oil fields in western North Dakota to Pakota, Illinois. It is designed to carry up to 570,000 barrels of oil per day. As of a month ago, it was 84 percent complete, with the Missouri River crossing being the unfinished link.

While listening to Jackson Browne perform at the concert at the Prairie Knights Casino, someone passed me a booklet about DAPL and the financing details regarding the oil that would flow through the pipeline. The ten-page, well-researched report was produced by Cathy Kunkel, energy analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, and Clark Williams-Derry, Director of Energy Finance for Sightline Institute. It was published last month.

It seems that oil production, similar to other extractive industries like mining, is subject to boom and bust cycles. The report contends that oil production in the Bakken region may now be experiencing the bust phase of the cycle and the pipeline could become what the authors call a “stranded asset.”

Energy Transfer Partners, the corporation behind the pipeline, proposed it in 2014 to transport oil from the “rapidly expanding Bakken and Three Forks production areas in North Dakota.” By mid-2016, DAPL had signed contracts for 90 percent of the pipeline’s capacity.

Phillips 66 signed a long-term commitment with DAPL and Marathon Petroleum announced its intention to follow suit. Phillips 66 and other oil companies announced plans to tie “collector” pipelines into DAPL.

The pipeline was originally proposed as a joint venture of Energy Transfer Partners and Phillips 66, the report says, but this past August ETP announced plans to sell 49 percent of its stake to a joint venture of Enbridge Energy Partners and Marathon. ETP would still hold the largest ownership stake. The report notes that the sale can’t be finalized until the Army Corps of Engineers grants its final easement on the project.

The pipeline was originally proposed as a joint venture of Energy Transfer Partners and Phillips 66, the report says, but this past August ETP announced plans to sell 49 percent of its stake to a joint venture of Enbridge Energy Partners and Marathon. ETP would still hold the largest ownership stake. The report notes that the sale can’t be finalized until the Army Corps of Engineers grants its final easement on the project.

Meanwhile, prices for crude oil dropped from about $95 per barrel in 2013-14 to below $75 per barrel in December, 2014. Bakken drillers are cutting back on capital expenditures and production. Whiting Petroleum, one of the largest Bakken drillers, cut its capital budget for exploration and development by nearly 80 percent this year. “Recent forecasts of global oil prices do not suggest any recovery of Bakken oil production for at least a decade,” the report notes. “The World Bank’s forecast of oil prices through 2025 does not show oil prices climbing above $70 per barrel.”

Financial regulators have warned that aggressive acquisition and exploration by oil and gas companies from 2010 to 2014 led them to assume “unsustainable debt,” leaving them vulnerable when commodity prices collapsed. The Bakken drillers are confronting serious financial problems and three of the top companies have experienced credit rating downgrades.

The report goes on to argue that the Bakken already has sufficient pipeline, rail facilities and local refineries to handle all the oil it produces. The region’s oil transport infrastructure is already overbuilt, it says, with about 60 percent of its capacity currently unutilized.

Since shipment of Bakken crude to the Pacific Northwest via rail has remained steady, “DAPL capacity could become superfluous by mid-2017. Unless oil prices spike and Bakken production rebounds promptly, the region may soon find its oil pipeline capacity is already overbuilt, even without DAPL.”

Since shipment of Bakken crude to the Pacific Northwest via rail has remained steady, “DAPL capacity could become superfluous by mid-2017. Unless oil prices spike and Bakken production rebounds promptly, the region may soon find its oil pipeline capacity is already overbuilt, even without DAPL.”

All these factors, as well as a unique investment structure–master limited partnership (MPL)–have put ETP in a bind. In an MLP, a large portion of revenue is pledged as distributions to equity investors and distribution growth is key to attracting new capital. ETP has been in a phase of rapid, high-risk growth, requiring it to raise capital quickly. Its assets grew from $4.4 billion in 2005 to $65.2 billion ten years later. The company is currently the lead developer of four other pipeline projects besides DAPL. In June of this year, Moody’s put ETP on a “negative outlook” due to its high leverage.

In papers it filed for the court case brought by the Standing Rock Tribe, ETP said it had made commitments to nine oil shippers to have the pipeline in place and operating by January 1, 2017. “These costs cannot be recovered and loss of shippers to the project could effectively result in project cancellation,” an ETP representative stated in a court document.

Camping Out

On Wednesday morning, with some help from new friends, we dig our car out and drive back to the Standing Rock camp. One of the first things we do is to attend one of the regularly scheduled direct action training sessions. It takes place by the Red Warrior Camp, in a one-room building warmed by a wood-burning stove. About 55 people are crowded into the little structure.

A woman from New Orleans who is a medic and part of the “decontamination unit” here demonstrates how to assist a person who has been subjected to pepper spray, mace or tear gas. Later, we go outside and practice how to protect each other when we are confronted by the over-zealous North Dakota law enforcement.

Remember not to antagonize the police, the trainer cautions. “No violence. Our goal is to protect the water, stand our ground. The people who live here will have to live with the aftermath for decades to come.”

My companion helps prepare meals in one of the kitchens while I explore the camp and attempt to photograph. My camera is tucked inside my jacket, nestled under a scarf, and I have a hand warmer inside each of my gloves.

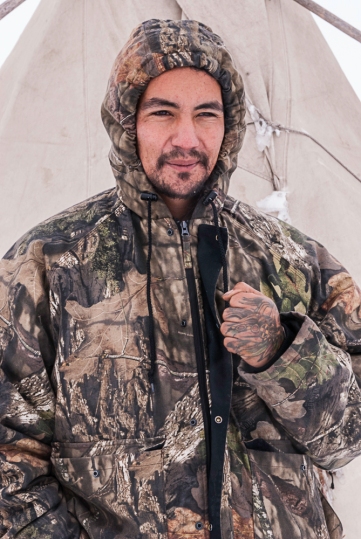

On one of my walks, I meet Joseph Romandia. He is with the Chumash tribe, people of coastal California. He left California to escape the gangs, he says. He lived in Wisconsin for a while, but now makes his home on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, where he works with youth and makes drums out of animal hides in order to support his family. He tells me about the third world conditions at Pine Ridge–the poverty and health problems–and I check some of the statistics later on my computer: one of the poorest counties in the United States, unemployment rate of 80 to 90 percent, alcoholism rate as high as 80 percent, life expectancy the second lowest in the hemisphere, trailing only Haiti.

Why are you here? I ask. “Because we drink from the same river at Pine Ridge that they drink from here,” he replies.

Joseph Romandia

Like Joseph, many of the people here have brought their families along. Dozens of children are sledding down a hill; some older ones are hitching a ride behind an auto, a dangerous sport that I too used to play as a teenager. And there are camp dogs, big and small, playing their doggy games.

I continue walking and meet Clarence, an imposing man from Wounded Knee. He is standing by his car with his wife and children. The car is jacked up, waiting for a new tire. I ask him how long he has been at the camp. “Since August,” he responds. How long will you be staying? I ask. “Until it’s over,” he says.

There are native people from all over the country here. There are also white, black and brown people from all over the country. More than a few people have come from other countries. Walking down the main road, I meet Julie, a young woman who hails from Paris, France. She tells me this is the second time she has flown here to spend time at the camp.

The people I meet, despite the cold, are warm, determined, resilient and confident. They are water protectors but they are also caretakers. I’m not certain if it is a skill they have always known or something they learned in the camp, but it seems their nature to look after each other. Something remarkable is happening here.

That night, we bed down with our sleeping bags on the dirt floor of the geodesic dome. Others gather around us and do the same. A man approaches, concerned for our comfort. He finds a large fleece blanket and covers us with it. The elders are still singing down by the sacred circle when we fall asleep.

About six in the morning, we wake to the sound of someone speaking on the PA, a funny but persistent monologue goading us to action. Good morning DAPL, Good morning CNN, Get up, time to pray, We can’t slay the black snake if you stay in bed all day, When I was a kid, we used to walk ten miles … and on and on, a native version of Robin Williams in Good Morning Vietnam.

Soon we join a circle of prayer down at the campfire. Then we are instructed to each take some tobacco and sage and we walk in quiet procession down to the Cannonball River, with the elder women leading us. At the river, one by one, we sprinkle the tobacco and sage on the water and we sing songs. Another day at Standing Rock has begun.

▪ ▪ ▪

Postscript

I wrote most of this on Sunday, as snow was falling in Wisconsin. The Sunday before, we had just arrived at Standing Rock. The Sunday before that was “Bloody Sunday” on the bridge near Standing Rock.

This Sunday the US Army Corps of Engineers announced that it would not grant an easement to Energy Transfer Partners to complete its pipeline project. Instead, it would initiate an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process to determine if there are other feasible alternatives to the proposed project, such as rerouting the last segment of the pipeline.

Of course, this is reason to celebrate and is testimony to the courageous and creative organizing work of the Standing Rock Tribe, the Lakota and Dakota people, and all their supporters around the country.

But we should bear in mind that the Army Corps is the same Army Corps responsible for building five dams on the Missouri River in the 1960s, flooding over 200,000 acres on the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River reservations, submerging towns under Lake Oahe and displacing many native people.

We should also bear in mind that Donald Trump has substantial investments in Energy Transfer Partners and Phillips 66, (OOPS! It’s just been reported that he’s divested of his holdings in ETP, which could be even worse), and that Kelcy Warren, ETP’s chief executive, has contributed handsomely to Trump’s presidential campaign and the Republican Party.

I want to close by quoting the last paragraph of an essay written by Bruce R. Ough, resident bishop of the Dakotas-Minnesota Area of the United Methodist Church, an essay he wrote shortly after the Standing Rock Sioux filed their request for an injunction against the Dakota Access Pipeline this past summer:

Whatever the outcome of the court’s ruling, this may be the moment God is giving us all to come together, not as antagonists in bondage to our traumatic past, but as mutually empowered advocates for the common good and the sacredness of the waters and all of life. This may be the moment God has given us to use our power to define a just and life-giving future.

ALL PHOTOS BY TOM BOSWELL©2016. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.